13 to 16 July 2023

Porto Santo to Baia d’Abra, Madeira, 32 44′ 70″N 16 41′ 62″W, 28nm, 5 hours 40 minutes

to Caniçal, 32 44′ 03″N 16 44′ 23″W, 2nm, 1 hour

After a month in Porto Santo we were ready to explore somewhere new. Through Rene’s Olympic windsurfing connections we had secured berths for Pintail and Momentum in Funchal marina on Madeira from 17 July. The only problem was that in early June the torrential rain that came with Storm Oscar had sent tonnes of debris down the island’s storm drains and down into the harbour, blocking entry and exit to the marina. Dredging had been underway for a while but we were still uncertain as to whether our deep keels would squeeze in through the entrance.

While we waited for confirmation we headed southwest from Porto Santo to the bigger and more populous Madeira. We mostly motor sailed the 30 miles in calm winds and I confess to having very mixed feelings as we approached the mountainous outline of Madeira. It has long been the the favourite holiday island of my parents and I have very fond memories of them sharing their favourite places with me back in 2009. I would have dearly loved to have been able to meet up with them there. I know they do too.

The jagged peaks of Madeira emerged from a layer of cloud as we approached and are in sharp contrast to the more rounded peaks of Porto Santo. We were heading to an isolated anchorage tucked behind Ponta de São Lourenço, a spiny peninsula of bare rock that sticks out like a tail at the south east end of the island. So spiny, long and thin that it is known as the Dragon’s Tail.

At the base of the tail, where it meets the body of the island, Baia d’Abra is one of very few viable anchorages on the island. It is surrounded by sheer cliffs of pyroclastic rock that, at the same time as Porto Santo, where thrust out of the ocean by volcanic activity. The anchorage was already busy with four other yachts – always a good sign – but by the time Momentum arrived two had already disappeared. We sat staring at the multi coloured cliffs wishing we had paid more attention in our geography lessons and declaring it the most spectacular anchorage we’ve been to yet.

So much so that I decided it was a worthy location for my first swim of the summer!

Not content with staring at the cliffs from the sea, we hauled the dinghies up onto the small, steep and rocky beach and climbed up the narrow path to the top.

There were truly spectacular views in every direction but at quite a price to the vertigo sufferer!

More than occasionally the path took us very close indeed to sheer drops. When we reached the start of a very narrow ledge, like a horse refusing to jump, I simply sat down and refused to go further. My shaking legs and dizzy head had been tested too far!

We might look like we had the place to ourselves but this isolated headland was, in fact, far from isolated. Bus loads of hikers (and others in entirely inappropriate footwear) shuffled single file along the narrow path somewhat detracting from the splendour of it all.

To escape the crowds we took to the dinghy and had a ride along the bottom of the cliffs for a closer look at all the many layers, colours and shapes.

It may look lovely and calm but we endured a couple of really sleepless nights. Just as in Porto Santo, the katabatic winds roared down the cliffs sending us spinning around Pintail’s anchor. It was, however, a small price to pay for the privilege of staying somewhere so special.

The katabatic winds weren’t the only thing to go bump in the night. On our first night Stefan heard a very ghostly sound through the hull – something like a diver breathing right next to us. It frightened the life out of him but he kept it to himself. The next night we both heard the same spooky noise and just couldn’t work out what it could be. Then during the day Stefan spotted something near the cliffs that looked like a seal. Could it have been one of the monk seals that, although endangered, live in this area? And could it have been responsible for the strange breathing noises in the night? We like to think it was, rather than some spectre from the deep!

Challenging nights aside, we could have spent longer in Baia d’Abra. However, both the anchorage and the whale museum at Caniçal, just two miles along the coast, came very highly recommended. So we decided to move on and try them both out.

It was a short but very wet passage – our first experience of how Madeira’s weather can change in a flash. The cloud descended and more water than we had seen in a very long time fell from the sky – mostly on me at the helm! I was soaked through by the time the anchor was set just outside the harbour wall at Caniçal.

And when the cloud lifted, it was not just the weather that had changed. In those two miles we seemed to had been transported somewhere completely different. The bright green cliffs were in stark contrast to the bare rock we had adjusted to in Porto Santo. The landscape felt like it would be more at home in South East Asia. The brightly coloured houses recalled those of Italy. It all looked very far from Portuguese.

Caniçal is Madeira’s industrial port and other than its dramatic situation offers little to attract tourists – except, that is, a museum dedicated to the history of whaling in Madeira which had reviews that so belied its subject matter that we were intrigued to find out what all the fuss was about.

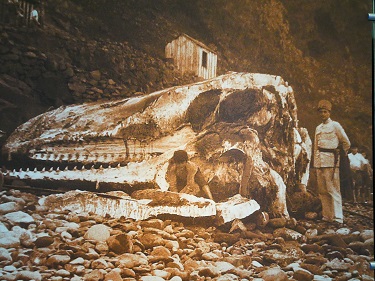

The interactive and multi media displays did not shy away from the barbarity of an industry established by a family business and operated between 1940 until it stopped in 1981.

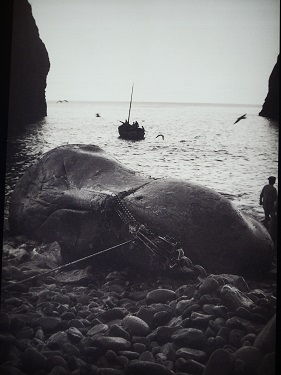

The horrors of whaling aside, it was impossible not to have a sneaking respect for the men who went out in a narrow wooden boat to catch beasts that were far longer and heavier. One flip of a tail or nudge from underneath by their prey could have sent the hunters into the water. Yet miraculously in forty years there were no fatalities.

It was also some consolation that of the whales caught and butchered on Madeira’s coast, very little went to waste. Blood, flesh and bone was made into animal feed and fertiliser. Ambergis, the non-digestible content of the whale’s stomach, was sold to the French perfume industry. Even the bones and teeth were used by artists to engrave and sell as Scrimshaw.

International bans on the use of whale products finally saw an end to whaling in Madeira in 1981 after what had been a comparatively short time but not before a noticable decrease in whale sightings around the archipelago.

And it was to man’s impact on whales, and their ocean home, that the museum’s focus quickly turned. Through a series of giant exhibits and 3D films, it charted the changes to feeding grounds and migration patterns of the world’s whales, large and small and the dangers of the volumes of chemicals and plastics released into our seas.

One animation charted the migration of a North Atlantic right whale mother and her calf and their struggle to find food in the changing temperatures of their ocean home. Weakened with hunger, and despite their superior size, they found themselves prey to a group of orcas.

‘There are few things as bad in the sea as killer whales‘ said the mother to her terrified child. We couldn’t help but concur!

It was an all round sobering but incredibly educative visit and, with whales and their fate very much on our minds, in an extraordinary coincidence, the very same day we heard that 55 pilot whales had washed up on the island of Lewis in Scotland…