7 to 13 February 2024

Étang Z’Abricot to Anse Mathurin, 14° 32′ 27″ N 61° 4′ 25″ W, 3nm, 1 hour

to Sainte Pierre, 14° 44.33′ N, 61° 10.65′ W, 14nm, 3 hours 45 minutes

to Anse Mathurin, 14° 32′ 27″ N 61° 4′ 25″ W, 14nm, 3 hours

to Les Trois Îlets, 14° 32′ 37″ N, 61° 1′ 65″ W, 5nm, 1 hour

to Sainte Anne, 14° 25′ 67″ N, 60° 53′ 32″ W, 20nm, 5 hours 30

In our travels in Europe we have been used to exploring ancient history, sometimes even prehistory, but the Caribbean was teaching us that history sometimes isn’t that long ago and that you don’t have to scratch the surface of the present very far to find the past.

And our next stop was going to take us to the location of the biggest natural disaster to befall Martinique in the 20th century.

But before we left the bay at Fort de France and while we waited for some favourable wind to sail north, we went back to the south of the bay and anchored off the beach at Anse Mathurin. Tucked behind Îlet Ramiers and in front of a deserted beach accessed only by a walking path from Anse a l’Ane, it was slightly less busy than the anchorages off Anse a l’Ane and Anse Mitan.

The beach promised a great location for our very first Caribbean beach picnic. The deserted beach wasn’t quite as deserted as we’d hoped despite our early start. A couple of dinghies were already parked up when we arrived but it was a quiet spot nonetheless and we ate our French delicacies whilst watching hummingbirds buzz around overhead.

After our picnic we went into Anse a l’Ane, where we had a rather strange encounter with the French Navy. As Stefan dropped me off on the dock, soldiers in full camouflage streamed out of a navy boat and took up positions all throughout the beach and town. Their camouflage worked really well – it was hard to spot them. My red dress, on the other hand, not so much. We wondered if we had missed an important news item about some modern day conflict in the Caribbean! We thought it best to make ourselves scarce.

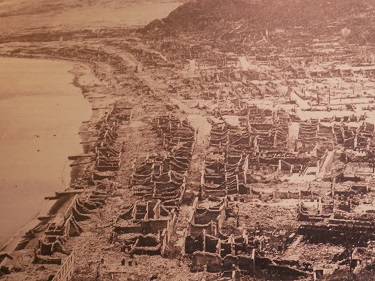

Arriving almost at the northern tip of Martinique, the skyline of Saint Pierre is dominated by the author of the disaster that befell the town in 1902, the ominous Mont Pelée volcano. As we arrived and settled on our mooring buoy just off the town the clouds cleared and we enjoyed a great view of this beast that razed the island’s then capital to the ground killing almost all of its inhabitants.

We were expecting heavy rain on Friday but instead when we woke there was just a gentle SW swell. We decided to have a wander in town and learn more about the eruption that had obliterated the town last century. However, when we got to the concrete dock the swell was too big and leaving the dinghy wasn’t going to be safe so Stefan dropped me off and I went solo.

Since the eruption Saint Pierre has been largely rebuilt. Many of the new buildings have been built inside the shells of the ruined ones. The town has never, however, regained its status as the capital. It is now a main street surrounded by maybe 3 or 4 blocks of houses back into the cliffs and not even 5,000 residents. It is, like so many in the Caribbean, a chickens-in-the-street kind of place.

Amongst the everyday life there are ruins of buildings almost vapourised by the eruption, left, as if the looming slopes of Mount Pelée weren’t enough, as a constant reminder of how fragile life in the shadow of a volcano can be. In Europe we became used to wandering very ancient ruins but here they are 19th and 20th century buildings, so familiar to a modern eye.

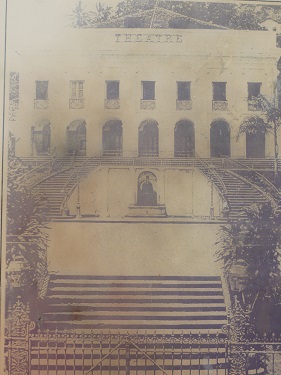

The blackened walls of the town’s theatre look out towards the slopes of Mount Pelée as though demanding an apology that never comes. Outside, the grand staircase is much as it was, just without the building facade at the top. Inside, the stone structures of the orchestra pit and stage are still visible.

From the theatre it was possible to look down into what had once been the local prison and the location of the most miraculous survival story. On 7 May 1902 Louis-Auguste Cyparis got into a fight in the streets of Saint Pierre and ended up in solitary confinement in a thick walled, windowless cell in the jail. When the pyroclastic flow spewed down on the town on 8 May he was protected from its worst and rescued four days later from the rubble. He went on to earn a living telling his amazing escape story as part of Barnum’s Circus.

A very moving museum is dedicated to telling the story of May 1902 and remembering the nearly 30,000 people who were not so lucky as Louis-Auguste. Everyday objects tell of the devastating heat of the eruption. In fact, scientists were able to gauge the extent of the heat by the responses of the various materials.

Carbonised food stuffs like cheese and coffee beans were found.

The centre of the museum stands as a memorial to the people who died during the eruptions, their names lining the walls from floor to ceiling surrounding the town’s buckled bell. It was a sobering reminder of nature’s sometimes devastatingly destructive power.

Little did we know, when Stefan picked me up, that we would be having our own encounter with that destructive power.

That troublesome swell got bigger and bigger throughout the day. By the time daylight was disappearing and we were clearing away the dinner things, Pintail was pitching from rail to rail and we discussed our options. By 8pm, it simply didn’t feel safe anymore and, despite the fact that we had yet to pay for our buoy, we decided to leave.

Without a breath of wind and just this mysterious swell, we motored back to Anse Mathurin. It was quite eerie. We had been convinced that with the direction of the swell the anchorage that had been so calm for us before would give us the best protection ee needed this time but by the time we got there it was clear the swell was creeping in. Too nervous to navigate the shallow shoals deeper into the bay in the dark, we anchored anyway. Everything always seems worse in the dark but we continued to roll quite dramatically and got no sleep. At 7am, with the daylight, we upped anchor and found our way through the shallows to Les Trois Îslets where the water was flat calm and we could stop worrying.

With some unexpected extra time on Martinique, we had an opportunity to explore a bit more.

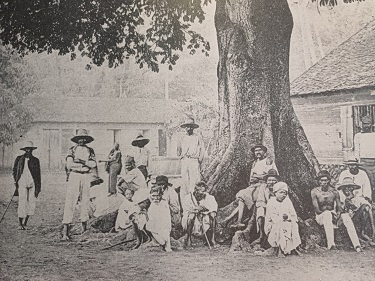

It had become curious to us that we had seen so little direct reference to slavery so far in the Caribbean. It felt like an enormous elephant in this room they call paradise and we had made the decision very early on to use our time in the islands to seek out the stories of those enslaved and brutalised by the colonial elite – to hear their voices and learn their stories rather than those of their captors. So, in Les Trois Îlets I sought out not the nearby palatial plantation home of Napoleon’s Josephine but the Maison de la Canne.

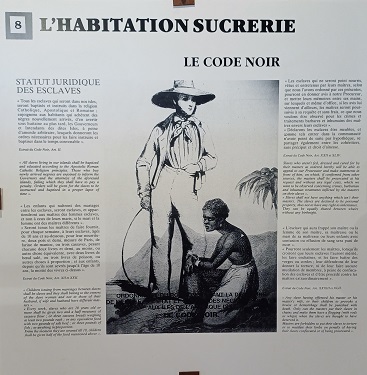

Sugar was the main industry of the Caribbean islands for three centuries with exports providing 80 to 90% of Western Europe’s supply. By the late 18th century, on Martinique there were 450 sugar factories and, as elsewhere around the region, the main source of labour was enslaved Africans. Life for slaves on the plantations under France’s Code Noir, setting out their legal status, treatment and conditions, was unimaginably cruel and, I suspected, nothing like the Disneyfied mock up of a slave hut in the museum.

Article XXXVIII. The fugitive slave who has been on the run for one month from the day his master reported him to the police, shall have his ears cut off and shall be branded with a fleur de lys on one shoulder. If he commits the same infraction for another month, again counting from the day he is reported, he shall have his hamstring cut and be branded with a fleur de lys on the other shoulder. The third time, he shall be put to death.

Extraordinarily brave uprisings by the slaves eventually saw an end to slavery in 1848 and plantation owners had to look elsewhere for labour. My French translation wasn’t up to the nuanced euphemisms of the museum’s explanation boards but I am fairly sure that although their migration appeared voluntary, the people who arrived from the French colonies of southern India were treated only marginally better by their employers. Today Martinique maintains a large population of Tamils descending from the indentured labourers who arrived in the late 1800s.

When the European market for sugar disappeared, sugarcane exports significantly reduced and is now confined almost exclusively to rum production.

Something that does remain from the end of slavery is Martinique’s days long Carneval celebrations and our extended stay on the island meant we were going to be able to experience it for ourselves…