6 to 9 November 2025

Through fields of cows, sheep and goats, we drove out of Georgia on Hog Mountain Road and into Alabama. Thick drizzle in the air reflected our mood the morning Trump declared the election won and there was the eeriest of atmospheres all around.

Alongside Murder Creek National Forest, a single lane highway took us passed the Shady Oaks mobile home community and the identikit, oversized, redbrick courthouses of the likes of Monticello, Forsythia and Talbotton. These places did not invite us to stop although Bob’s Discount Store did its best to cheer us a little at one crossroad and Flat Rock Park provided a very literal place for a rather damp picnic.

We were heading for Alabama’s State capital and arguably the epicenter of the civil rights movement. It’s relatively new Legacy Sites had come highly recommended and so we had belated changed our route and swapped the big city of Birmingham for the smaller but more historic Montgomery.

And any walk around Montgomery very quickly introduces you to the legends of the civil rights movement.

Rosa Parks might not have been the first to refuse to give up her seat to a white person (we see you, 15 year old Claudette Colvin) but, from her position as secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), she is rightly celebrated with sparking a wider bus boycott which forced the city to desegregate buses as well as wider protests against segregation in other public places.

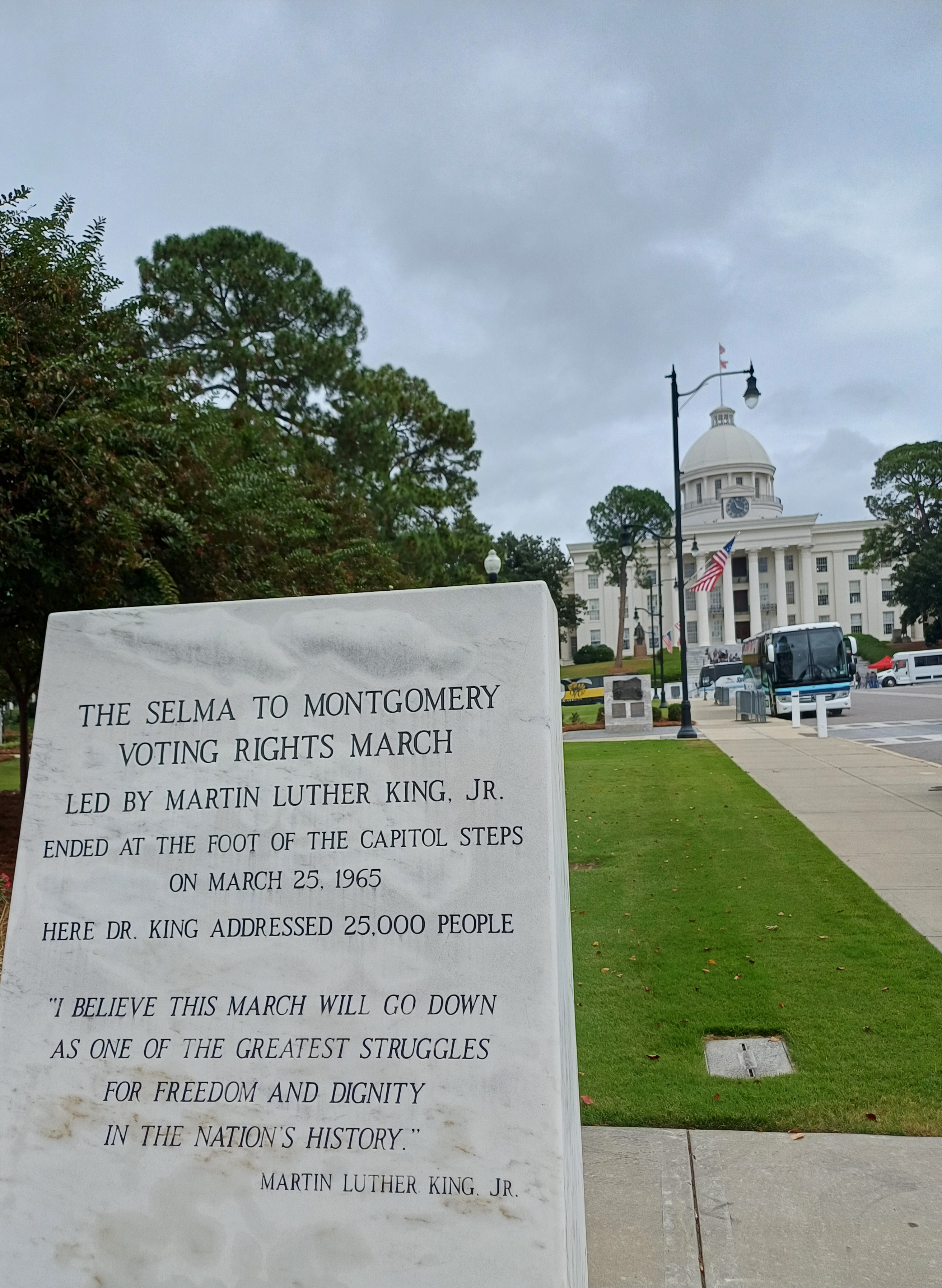

And of course, Martin Luther King Jr was pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church from where the bus boycotts and his Selma to Montgomery voting rights march were organised.

Reminders of the city’s links to the horrors of the slave trade and progress towards greater integration are everywhere but nowhere laid more bare than at the first of the Legacy Sites, the Legacy Museum.

Similar to the Memorial ACTE museum on Guadaloupe, in sometimes beautiful but always arresting artwork and displays, the museum told the story of slavery in the South. However, instead of telling the story of a move towards greater freedom, it takes you on a journey to the mass incarceration of Black people in the States. Using holograms and video screens you can talk to enslaved and incarcerated people. It tells a very different and important story about the reality of race equality across the country today.

After that very sobering visit we wandered into the centre of Montgomery. It’s a surprisingly small place and wasn’t long before we were at the Capitol building. Outside, on the steps, we bumped into a student demonstration. As they were dispersing we asked a group of them what the protest was about. Calling for scholarships for first generation college students to overcome the financial barriers to further education, came the answer. Good luck with that under the new administration, we thought, but the hope of better futures amongst all the division we had learnt about was so encouraging to hear.

And then just across the road from the Capitol we were confronted by yet another symbol of a country once brutally divided, the First White House of the Confederacy. We had already visited the Second White House of the Confederacy in Richmond, Virginia. We felt no need to step foot in this one.

We had ticked off one of the three Legacy Sites so in the afternoon we made an attempt to reach a second, the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park. Travelling on foot rather than via the shuttle bus, we found our path blocked by a quintessentially American sight, the railroad crossing. We waited for the stationary train to budge for about 10 minutes and then about the same amount of time for carriage after carriage of train to pass. With seemingly no end in sight and weighed down a little by the heaviness of the museum we decided to save the sculpture park for the next day.

We knew that the third of the Legacy Sites, the National Memorial of Peace and Justice, was going to be a difficult one but we were unprepared for beauty and scale of this memorial to the 4,400 plus Black people who were lynched between 1877 and 1950. More than 800 steel tablets name those killed by racial violence in each individual county. Those tablets from counties who have acknowledged the lynchings hang eerily yet beautifully from the ceiling in the main structure. Walking beneath them was one of the most powerful and sobering experiences. Those from counties that have not acknowledged their part in the lynchings lie like coffins side by side outside. The number of the latter demonstrated very clearly that this process of acknowledgment and reconciliation is very far from complete.

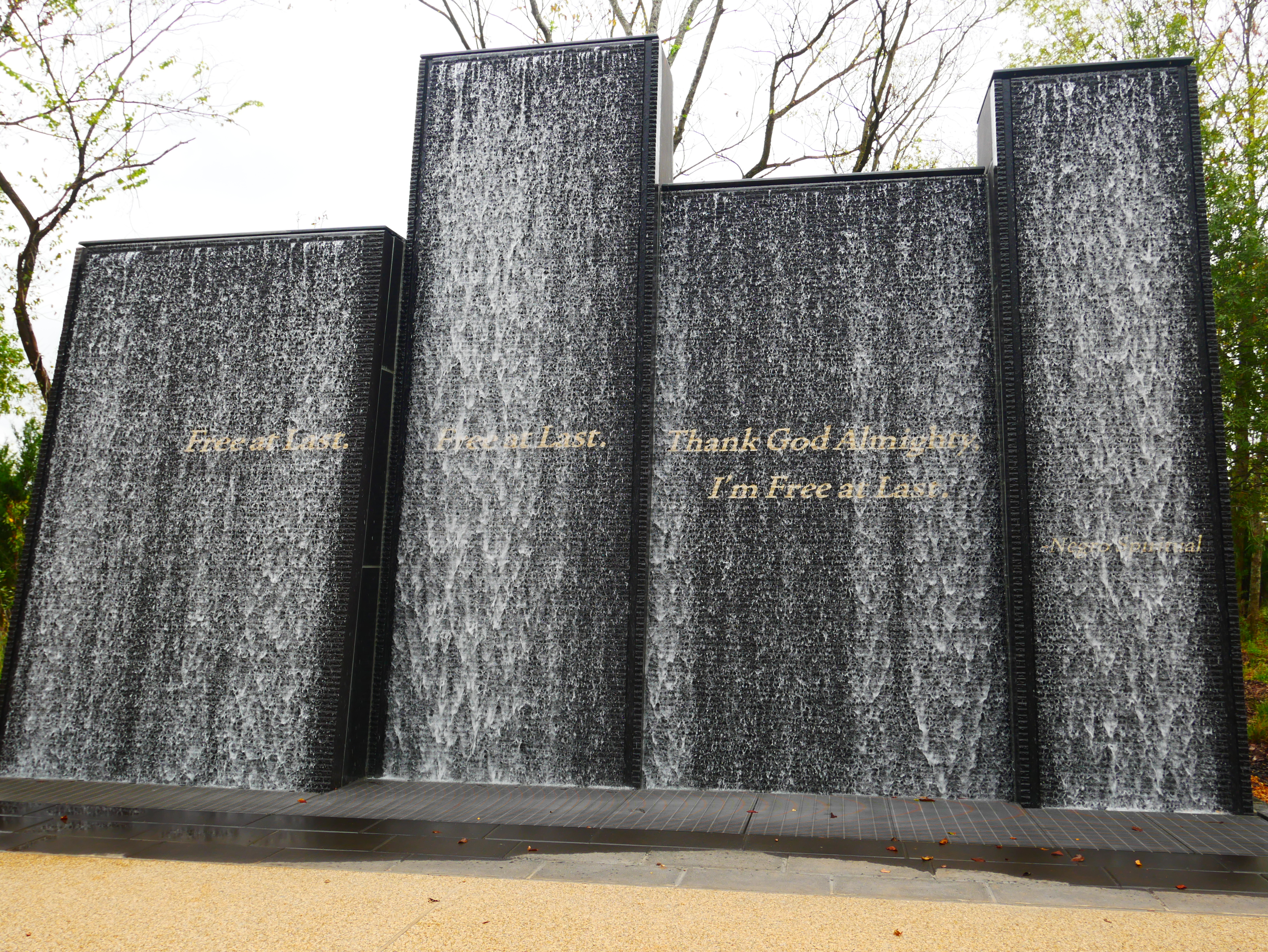

Before we left Montgomery we finally made it to the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park. Sitting beside the Alabama River and where photography was mostly forbidden, a winding path took us around some incredible works of sculpture telling the unflinching story of slavery, some very confronting and literal, like a whipping post and a train car used to traffic human beings, and some much more artistic expressions of the resilience and courage of people robbed of their humanity. The trail ends with a very moving memorial listing over 100,000 family names representing the millions of enslaved Black people – giving names to those whose identity once did not matter.

We were very glad to have made our detour to Montgomery and leaving towards Mississippi it also meant that we got to drive along the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, retracing (albeit in reverse) the route of the three 54 mile voting rights marches led by Martin Luther King Jr. in 1965. Alongside the iconic Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, we talked to the nephew of a man who had been at the start of one of those marches on 7 March 1965 when the police and locals attacked the marchers with clubs and tear gas on the bridge on what is now known as Bloody Sunday. This assault on the marchers’ non-violent action became a turning point in the civil rights movement and led to the passing of the Voting Rights Act, which by August 1965 enabled all African Americans to register to vote and to vote without harassment.

Today Selma is one of Alabama’s poorest cities where one in three people live below the poverty line and the grand old houses have fallen beyond repair.

From Selma we drove on through Alabama’s Black Belt. Named after the rich, black soil that led early settlers to develop a network of cotton plantations that relied on the labour of enslaved people, the area remains home to ‘the richest soil and the poorest people’. With the plantations gone, the Black Belt has become an area of economic disadvantage, unemployment and poor social services. The places we saw along the way left us in no doubt that inequality remains very much a reality for these Southern communities and we felt sure that the new President was not going to improve things one little bit…